Integrating Nutrition and Vaccination Efforts in Crisis-Affected Regions of Cameroon

Journey as a Health Professional

Ful Morine’s passion for healthcare began in childhood, shaped by her mother’s dedication to ensuring she received all her vaccinations. Her mother often shared the story of how she traveled for three days to complete Ful’s immunization schedule. This early experience left a lasting impression on Ful.

During her first year of primary school, a medical team visited to vaccinate the children. When Ful presented her well-documented vaccination record, the healthcare workers commended her mother for her diligence. These moments, combined with her own frequent battles with malaria and the absence of nearby health facilities, inspired her to pursue a career in medicine. She dreamed of becoming a doctor who could bring healthcare to the underserved children in her village.

After earning her Advanced Level certificate, she successfully enrolled in the Faculty of Health Sciences, where she studied Laboratory Sciences. Committed to making a difference, she began volunteering in her village, but she quickly became frustrated by the community’s reluctance to seek medical care. This realization led her to explore public health, recognizing that true impact lay in bringing services directly to communities rather than waiting for them to visit health facilities.

During her studies, one thought resonated deeply: “What we see in health facilities is just the tip of the iceberg of what is happening in the communities.” This conviction solidified her decision to focus on community health.

In 2016, Ful joined the Cameroon Baptist Convention Health Services (CBCHS), where her dedication was quickly recognized. When conflict escalated in the Northwest and Southwest regions, she was appointed Associate Administrator of Primary Healthcare and later became the Humanitarian Programme Coordinator. From that moment on, she would be at the front lines, leading essential health, nutrition, child protection, and WASH initiatives in some of the most crisis-affected communities.

Background

In the conflict-ridden Northwest and Southwest regions of Cameroon, children remain among the most vulnerable populations. Since the onset of the armed crisis in 2016, these regions have experienced significant socio-economic destruction, widespread displacement, and a deteriorating health infrastructure. Many health facilities have been destroyed or abandoned, leaving a few operational ones run by unskilled community health workers (CHWs) who struggle to meet the community’s needs.

At the end of 2018, Ful was appointed to lead the humanitarian response in crisis-affected regions of Cameroon. While she was eager to be in the communities where the needs were greatest, she also faced overwhelming security challenges. Health facilities had been burned down, healthcare workers attacked— some were maimed, others even killed. Yet, she knew she couldn’t turn away. She asked herself, “If you sit back, who will do it?” With that conviction, she took the lead.

Adding to the crisis, malnutrition rates have surged recently, with a Global Acute Malnutrition (GAM) rate of 5.7% and seven out of 39 health districts reporting high malnutrition vulnerabilities. Simultaneously, vaccination coverage has plummeted, evidenced by measles outbreaks in nine districts in 2023, indicating a concerning rise in zero-dose and under-immunized children.

Intervention

In response, the CBCHS, supported by UNICEF, launched an integrated nutrition and immunization response in 2024. This innovative initiative aimed to simultaneously address malnutrition and low vaccination coverage by leveraging existing nutrition programs to reach children who missed critical vaccines.

One of Ful’s first and most daunting tasks of this response was negotiating access with Non-State Armed Groups (NSAGs), who viewed healthcare services as a threat to their agenda. She started dialogue by looking out for the network of influence of the NSAGs, engaging them in discussions around the importance of providing humanitarian aid to the vulnerable populations and asking for opportunities to meet with their leaders. During the face-to-face discussion sessions, she emphasized the neutrality of humanitarian response and tactically highlighted how humanitarian aid was beneficial to the populations the NSAGs claimed to be fighting to protect. She elaborated that people who say they are fighting to protect their people should not deny aid.

One of Ful’s first and most daunting tasks of this response was negotiating access with Non-State Armed Groups (NSAGs), who viewed healthcare services as a threat to their agenda. She started dialogue by looking out for the network of influence of the NSAGs, engaging them in discussions around the importance of providing humanitarian aid to the vulnerable populations and asking for opportunities to meet with their leaders. During the face-to-face discussion sessions, she emphasized the neutrality of humanitarian response and tactically highlighted how humanitarian aid was beneficial to the populations the NSAGs claimed to be fighting to protect. She elaborated that people who say they are fighting to protect their people should not deny aid.

In one of such instances, with much determination and courage, she initiated dialogues and successfully secured access. In her words, “In one of the instances, I met with the NSAGs general and during our discussion, I told him he could not kill diseases like malaria, diarrhea etc. with a gun but humanitarian aid workers could do that. I pointed out to him that he could win the war but will not have people to rule if he allows diseases to be killing his people and he is refusing aid in the name of protecting his people. He confessed he never saw humanitarian aid that way and granted me and my team free access to his communities.” Though it was one of the most difficult undertakings of her career, it was also the most fulfilling. She witnessed children — who otherwise might have succumbed to malaria or vaccine-preventable diseases — receive life-saving care.

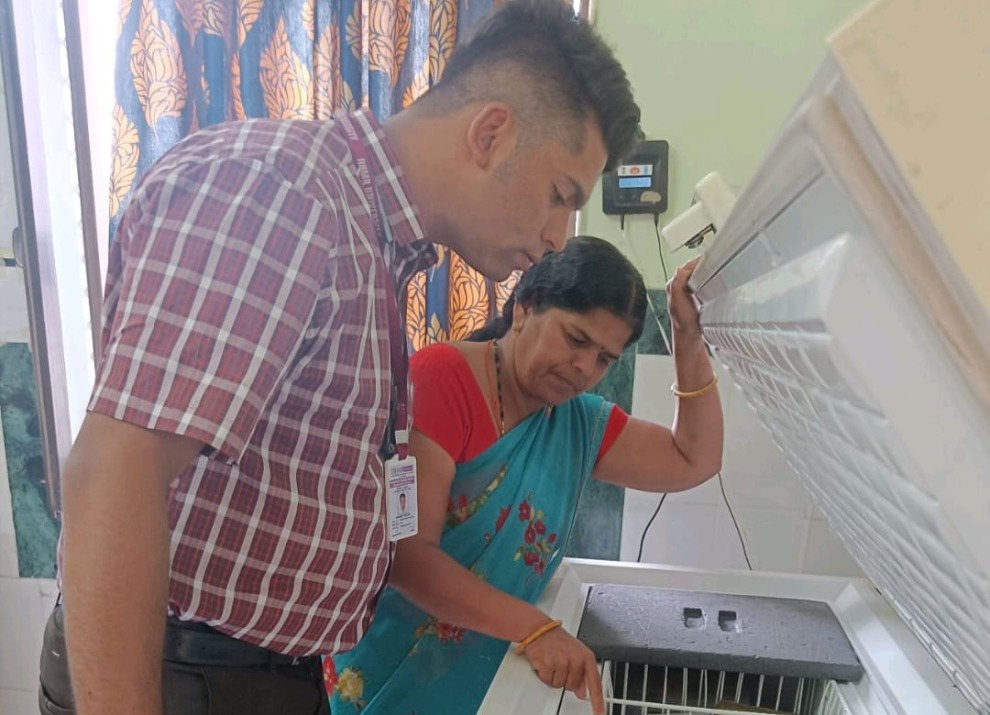

Each day in the field brought new risks, but Ful remained undeterred. Traveling by motorbike or trekking long distances, she and her team reached communities where displaced families had sought refuge. Their work began with sensitization and community engagement, ensuring that families understood the importance of good health practices. Together with Community Health Workers (CHWs), they conducted door-to-door screenings for malnutrition in children aged 6-59 months and provided infant and young child feeding counseling (IYCF-E) to pregnant and lactating mothers.

Beyond nutrition, the team focused on hygiene education — teaching families about sanitation, waste disposal, and environmental hygiene. These efforts helped build trust within communities, creating an environment where families were more open to discussing other health concerns, including immunization. Assessing children aged 0-59 months for vaccination status became a core part of their work. When they encountered vaccine-hesitant families, they engaged them in meaningful discussions to address concerns and promote vaccination as an essential health practice.

For children needing vaccinations, Ful and her team coordinated with local health facilities to provide immunization services. In cases where families had resettled in areas without nearby health facilities, they took proactive steps — bringing trained nurses or CHWs with vaccination skills to administer the vaccines. The main challenge remained securing vaccine supplies, but strong collaboration with health facilities ensured access to necessary resources and proper data reporting into District Health Information Software 2 (DHIS2).

Ful, and other trained CHWs conducted door-to-door campaigns, screening children aged 6-59 months for malnutrition using MUAC tapes, sensitizing families on vaccination and nutrition, and reviewing children’s vaccination records. They also engaged vaccine-hesitant families using Social and Behavior Change (SBC) strategies. Children in need of vaccines were referred to nearby health facilities or vaccinated through mobile clinics in collaboration with healthcare providers. Some challenges include accessing newly displaced communities, limited cold-chain equipment, requiring multiple vaccine carriers per day, and safety risks reaching remote areas. Regardless of challenges, Ful and her team were able to achieve impactful results.

Ful, and other trained CHWs conducted door-to-door campaigns, screening children aged 6-59 months for malnutrition using MUAC tapes, sensitizing families on vaccination and nutrition, and reviewing children’s vaccination records. They also engaged vaccine-hesitant families using Social and Behavior Change (SBC) strategies. Children in need of vaccines were referred to nearby health facilities or vaccinated through mobile clinics in collaboration with healthcare providers. Some challenges include accessing newly displaced communities, limited cold-chain equipment, requiring multiple vaccine carriers per day, and safety risks reaching remote areas. Regardless of challenges, Ful and her team were able to achieve impactful results.

Results

This integrated approach yielded promising results between March to June 2024:

- 20,932 children screened: 10,193 boys and 10,739 girls aged 6-59 months.

- Malnutrition management: 988 SAM cases (457 boys, 531 girls) and 2,002 MAM cases (931 boys, 1,070 girls) were treated.

- Vaccination coverage: 473 zero-dose or under-immunized children received vaccines, including 79 infants (0-11 months), 107 toddlers (12-23 months), and 287 older children (24-59 months).

- Addressing vaccine hesitancy: Out of 12 identified vaccine-hesitant families, 91.7% consented to vaccination after SBC engagement.

Lessons Learned

- Face-to-face engagement matters: Door-to-door interactions provided deeper insights into barriers to vaccination, including cultural and logistical challenges.

- Nutrition screening as an entry point: Identifying malnourished children highlighted zero-dose cases, demonstrating the value of integrated health interventions.

- Community involvement: Engaging entire communities, including fathers, fostered collective decision-making and improved acceptance of vaccination efforts.

- Collaboration is key: Coordination between CHWs and health facilities ensured effective referrals and improved vaccine access.

Ful’s experience reflects an unwavering commitment to improving immunization coverage in crisis settings. Despite persistent challenges, Ful and her team continue to innovate, recognizing the life-saving potential of vaccines and the urgency of preventing outbreaks of vaccine-preventable diseases. Her story is a testament to the power of integrated health services, bringing hope and resilience to the most vulnerable communities.

Recommended for You

We make vaccines more accessible, enable innovation and expand immunization across the globe.